Next week, I will be issuing practical completion on the first project I have finished with in-situ concrete. There have been lessons over the design, detailing and construction stages of the project, but I want to cover the key technical issues related to in-situ concrete.

Sample

I asked the contractor to pour our concrete mix into a 600x600x600 mould. This meant we could judge the corner conditions, surface finish and formwork joints and adjust our strategy accordingly. The cement was 40% OPC and 60% GGBS with a water cement ratio of 0.5 and cement to aggregate ratio of 1:6. We used 18mm thick MDO film faced ply for formwork and applied two coats of release agent and still used a layer of mesh in the sample. We removed the formwork after 48 hours, but the sample was still drying, it took three further days for the colour to stabilise. The colour with the mix set out above was like a light marble, with a smooth glossy finish, like poured stone. The common method is to silicone the joints between the formwork sheets, however upon testing the contractor realised that the joints are much neater if we use wood filler as opposed to silicone and butt the sheets together as closely as possible.

Reinforcement

Sometimes the main contractor can take over this element, but it is important to ask the structural engineer to price for a full set of reinforcement drawings with rebar schedules. Our contractor needed guidance here and we had to ask the engineer to prioritise this while works had started on site. The kitchen island in the project is also in-situ concrete with dramatic cantilevers, which required careful setting out- concrete is great in compression but terrible in tension hence the requirement for steel rebar.

Formwork

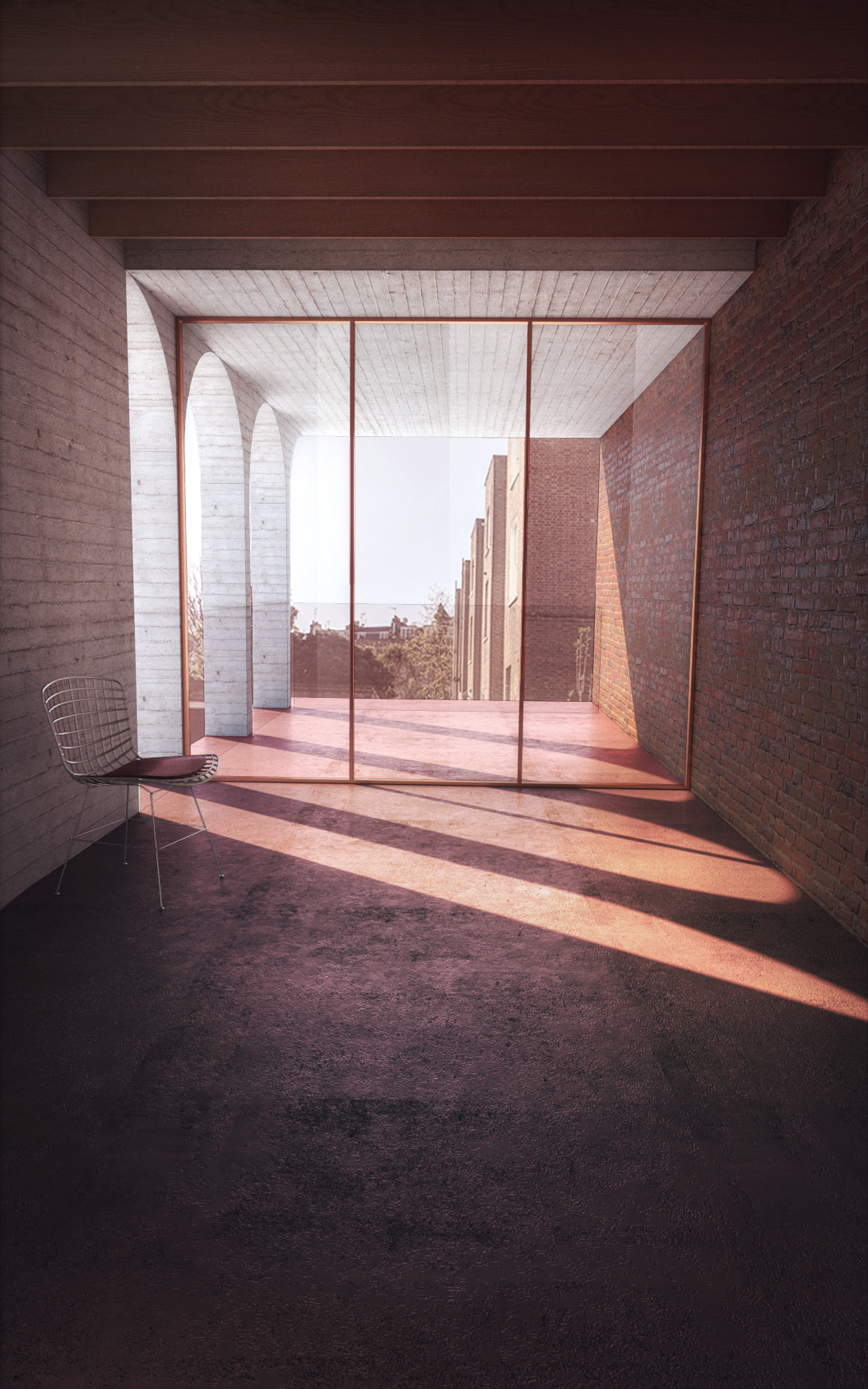

Once the formwork material is finalised, detailed drawings are required setting out the formwork sheets. No matter how neatly you fill between sheets, it is inevitable that joints will be visible considering the pressure of the concrete once poured. I set the sheets out based on the rhythm of the elevation/columns and lining through with the rooflight upstands in the exposed concrete soffit. Consequently, even where the joints are a bit raw, it looks intentional as they line through with a column, window or rooflight opening. One must watch that the film face isn’t wrinkled, or edges curled while checking all fixings before concrete is poured. The formwork requires two coats of release agent throughout, I specified Nufins Chemlease watching that excess was wiped away after two coats. This process needs to be super neat, waiting for the first coat to dry before applying the second, otherwise there is risk of surface retardation on the concrete face.

Temporary Works

The contractor took this on and used their experience. At one point you could barely walk through with the amount of acrows holding up the concrete ceiling. Additionally, an extensive timber structure had to be built, just to support the formwork and retain the pressure of the concrete once poured. However, we didn’t use clamps and in certain places the concrete slightly bowed, perhaps only visible to the architect. Ideally, a detailed temporary works design should have been undertaken before works began but this is driven by the scale and budget of the project too.

Shadow Gaps

I had to contend with two party wall conditions, so packing out the formwork and creating shadow gaps against these junctions was successful in elevation. However, I also had shadow gaps at the column to soffit intersection, which were created by using a glazing bead. This was too fussy for the material in retrospect, as they took off the formwork, they had to chisel the gaps out and it was difficult to execute clean lines. Shadow gaps in concrete should only be used where critical and the dimensional tolerance should be bumped up to 20mm to achieve clean edges.

Thermal Breaks

An exposed concrete soffit at 200mm thickness, obviously results in a significant cold bridge at the window head in this case. The engineer and I got around this by using ancon thermal breaks which are used on large projects between the floor structure and external balconies. These had to be welded to the rebar and set out carefully so the depth of the window frame would conceal them in the soffit. The lead times on these can be significant and this held us up from pouring for a while, so my advice would be to factor this in very early.

Sequencing

We poured the columns, commenced vibration, then poured the ceiling & upstands in one hit. In retrospect this could have been broken down further. The upstands were high to take the roof build-up and the concrete was just falling into the soffit formwork as they tried to pour these. It would have been a lot easier if we had waited for the ceiling to dry, set out a joint forming a drip in the soffit and then poured the upstands at parapet and rooflights.

Compaction

Once the concrete is poured, 30mm electrical pokers are inserted to vibrate the concrete and fill the mould. It’s important to not have there too close to the formwork, as this can result in poker burns and colour variations. They are usually inserted for 20 seconds- it’s important to withdraw the poker heads really slowly to remove all trapped air, removing too quickly can result in large blow holes trapped on the form face.

Sealing

This is the very last step, at the end of the project after the concrete has fully dried. The colour of the concrete actually continued to change quite significantly over a few weeks. Two coats of sealer should be applied to all internal and external exposed concrete surfaces. I specified Facael Oleo by Ethical coatings to provide a water repellent, vapour permeable seal to the surface. Additionally, the detail at the parapet used liquid applied waterproofing (Triflex Prodetal), hence no flashings are visible in elevation, providing concrete edge at the top of the building.

Overall, I think I understand the nature of the material much more than I did before. My instinct architecturally was to tightly control every aspect of the work, thinking this would result in an aesthetically pleasing and refined finish. However, with in-situ concrete the elements that you try to “design” are also the areas that will backfire on you tremendously. The most enjoyable parts of the finish are actually the areas that are a little flawed- the small blow holes, an expressed formwork joint, subtle variations in colour and aggregate and disparities in quality of reflected light.