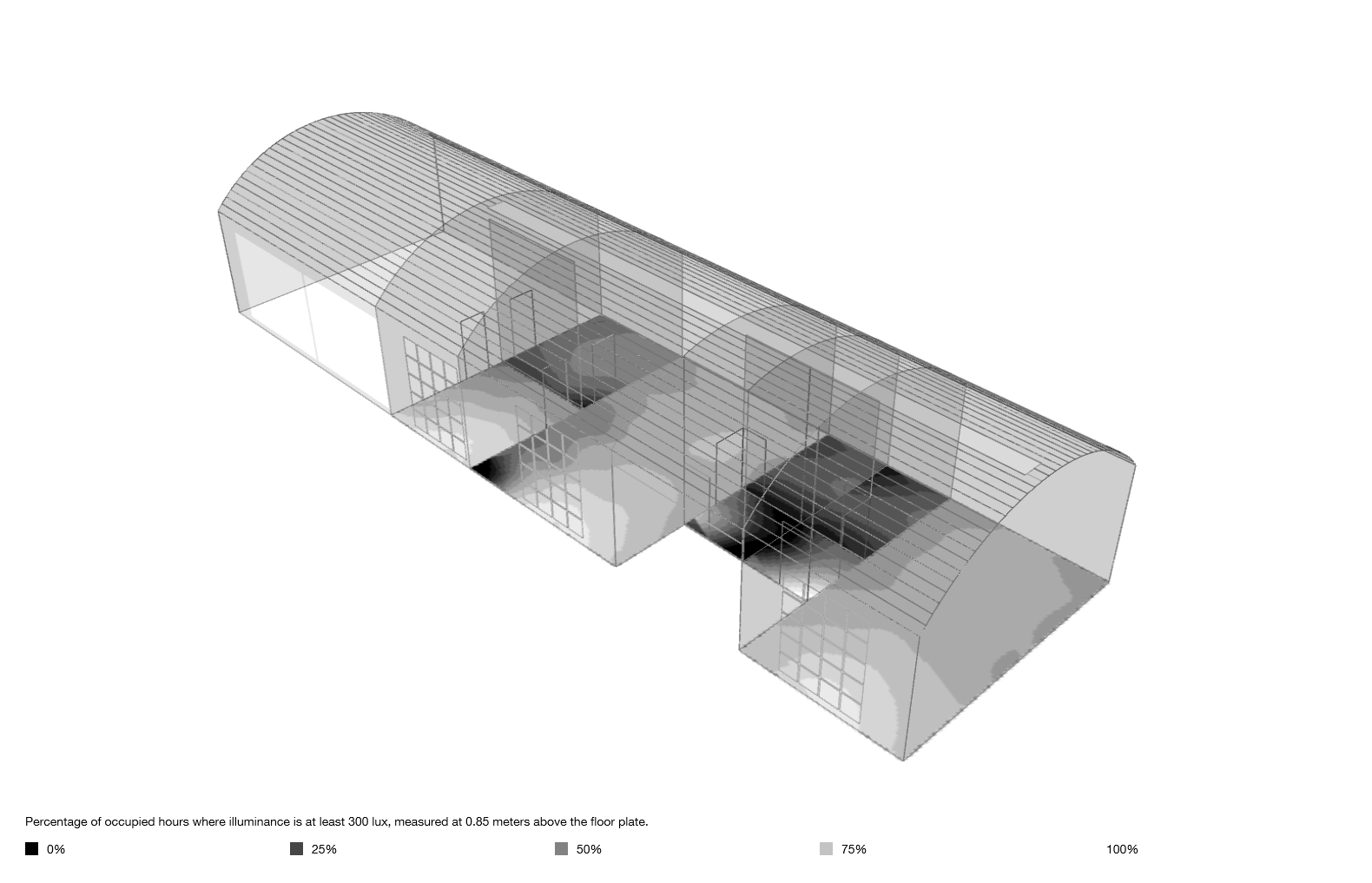

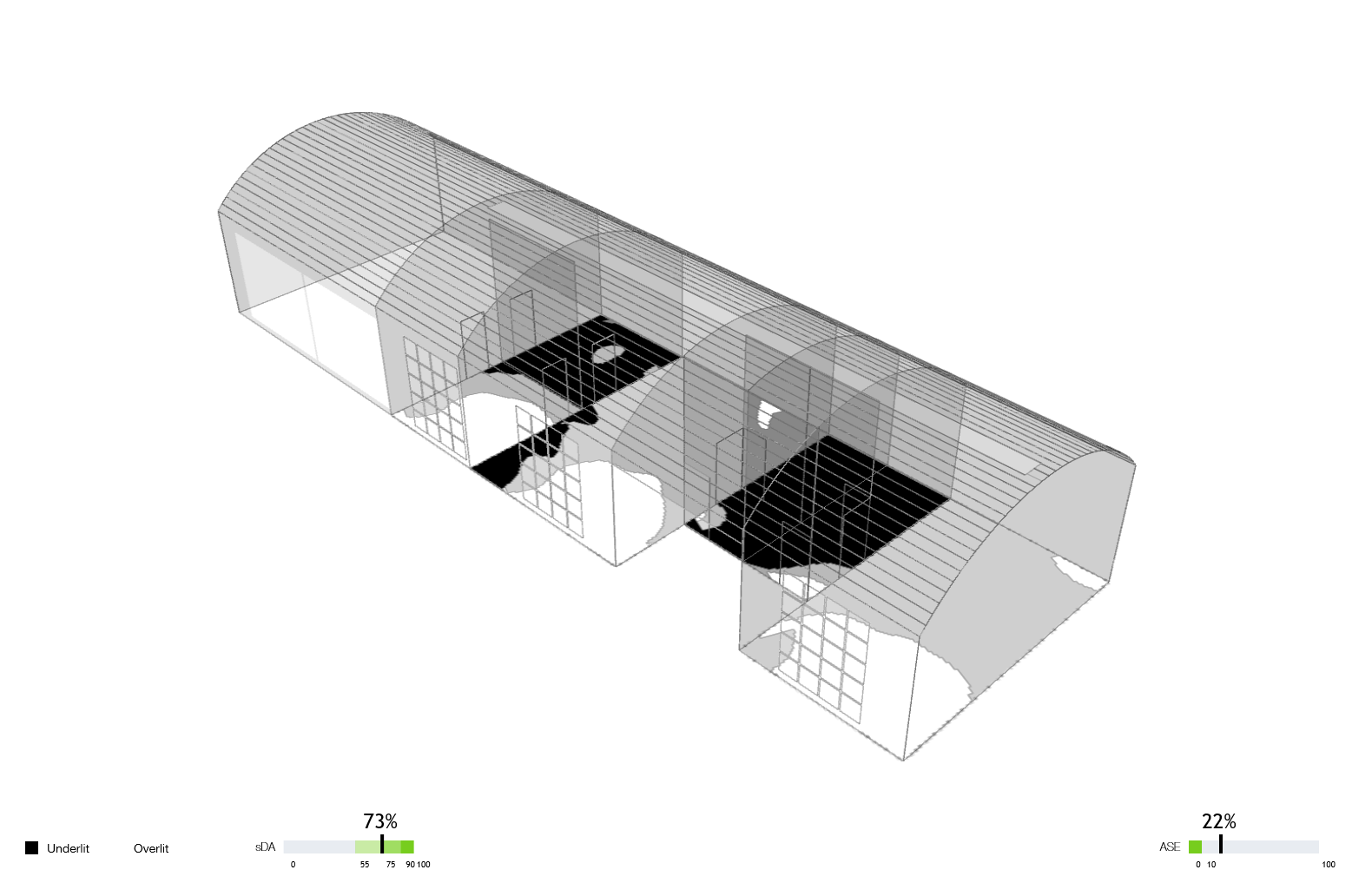

For the past few years, I have been experimenting with daylight analysis and energy models on projects at concept design stage. The first step is a general analysis of daylighting, which can be measured in Lux as seen in the first diagram. This metric summarises the performance throughout the whole year considering design, location and weather. A value of 300 Lux or above is usually desirable for homes, so you can check if you will have issues in any of the spaces and adjust the design accordingly. However, this is more of a general check as I do not necessarily want to obliterate every corner with maximum daylight, usually aiming for a composition of darker and lighter spaces. The annual daylight metric can be summarised into a diagram of over and underlit spaces as shown in the second image. In this example, I amended the design by moving entrance lobbies with an additional strip of rooflights toward the northern edge.

The second image shows the Spatial Daylight Autonomy (sDA) analysis. This describes how much of a space receives enough daylight, summarised as the percentage of floor area that receives the minimum illumination level for a minimum percentage of occupied hours. For example, if a space receives at least 300 Lux for at least 50% of the time it will be occupied. It is a climate-based analysis, based on a location specific weather file and is an accurate predictor of as built performance. A value of 55% is considered adequate and above 75% is considered excellent. In the example I used sDA to provide a quick snapshot as I developed the design, adjusting glazing volumes and floor to ceiling heights accordingly.

Annual Sun Exposure (ASE) is showing you how much of a room is getting too much sun which can cause visual or thermal discomfort. It’s similar to sDA but it measures the percentage of floor are that receives 1000 Lux for at least 250 occupied hours in one year. It can be a useful indicator of thermal comfort issues, but worth bearing in mind that it’s only measuring sunlight. Ideally you want under 50%, but my experience indicates that this can be difficult and not necessarily desirable in most cases- particularly passive solar designs relying on direct sunlight during winter months.

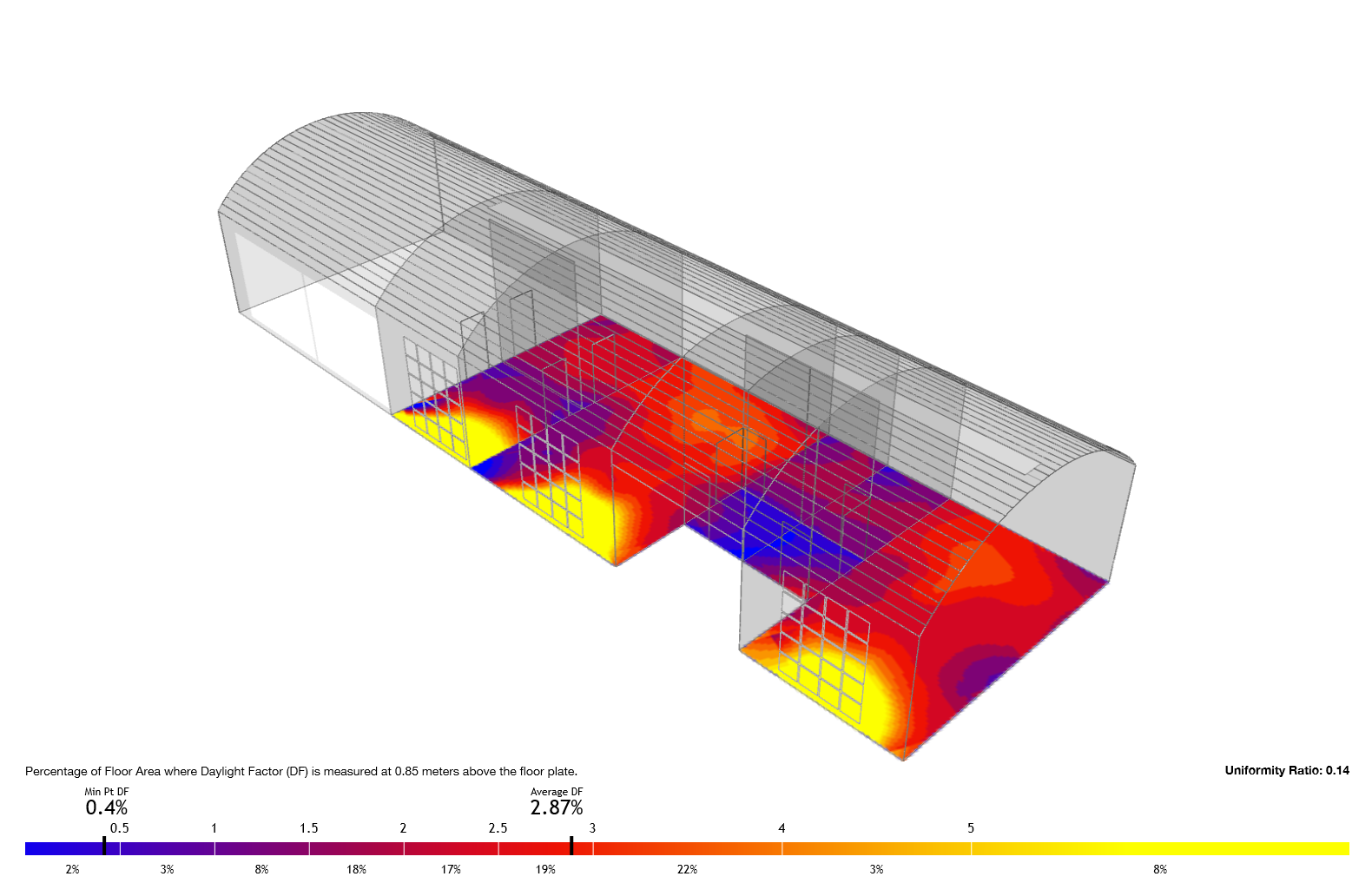

The second series of tests is concerned with the atmospheric or poetic quality of lighting as opposed to a purely numeric analysis. Daylight factor is an annual simulation of the daylight ratio under overcast sky conditions, providing the worst-case scenario of a design. It also considers ground reflections, window transmittance, and interreflections from room surfaces. Generally, 2% and above is considered acceptable for most spaces. However, this is also the most interesting analysis, as it clearly highlights the most poetic spaces that are fluctuating in daylight factor. For example, if one was to take a daylight factor analysis for a cathedral, it would not look dissimilar to what’s illustrated for the living spaces for this proposal. The values and fluctuations seen in the proposed living space are comparable to the quality of light found in some galleries and museums.

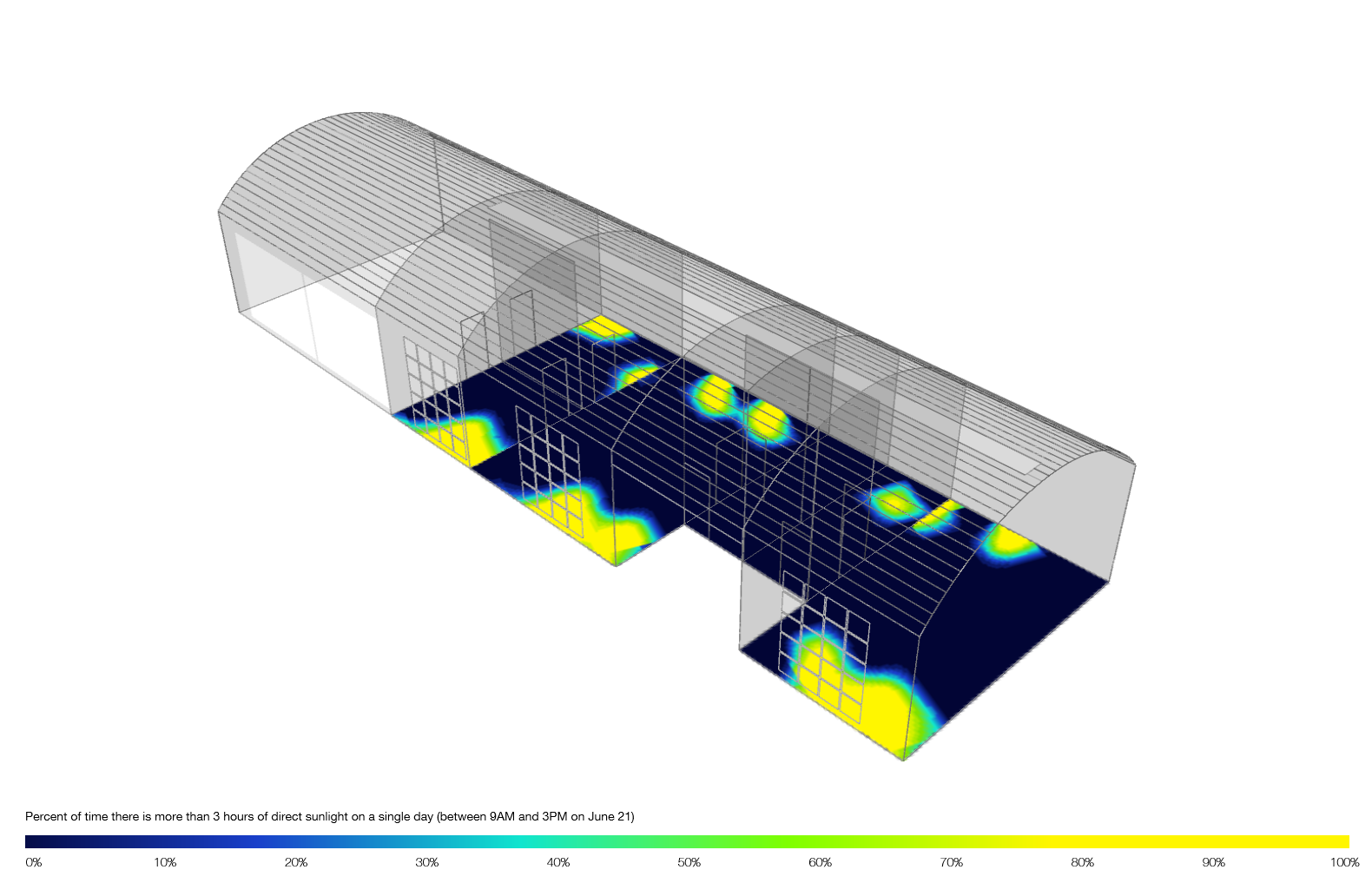

I also looked at the direct sunlight hours during the winter months, as illustrated in the second diagram. This confirms the ambition for the passive thermal strategy, where placing a control mechanism in the roof will aid the heating and cooling of the dwelling. For this project, this analysis fed into a strategy relying on thermal mass with the winter sun alongside stack via roof openings in the summer months. At this point I would also create a simple energy model. In this case, a draft analysis revealed a predicted energy use of 145 kWH/m² per year. This is a 48% reduction in energy use as the existing traditional structure with no insulation would use an estimated 300 kWH/m² per year. This can be refined further at technical design stage by looking at element performance. To give a simple example, you may see that the wall conduction is having a bigger impact on the heating load than the glazing specification. To reduce overall energy use it would be more productive to beef up the insulation by 50mm as opposed to going from double to triple glazed windows etc.

I have worked with analysis tools and have had a keen interest in Bioclimatic Design for some time, but recently became relaxed on the importance of this level of analysis, maybe because it is not a Building Regulations requirement. The Standard Assessment Procedure required by the Building Regulations literally means nothing- it is not location specific and does not even take occupancy factors into account, blindly pushing toward renewables despite context. I think it’s important to get away from this tick-box approach toward sustainability. Regardless, I wrote this to remind myself that any successful strategy toward reducing energy use must start from the outset.